September 28, 2025

The launch of Digital PAYG (“pay as you go”) trials on National Rail has been grabbing mainstream media headlines, and attracting the interest of many of those working in fare collection.

Positioned as an alternative to London style contactless PAYG, these trials use customers’ mobile phones to establish which journey(s) have been made, and retrospectively charge the best fare(s) for the day’s journeys.

Inevitably the launch has raised queries across topics such as reliability, privacy and inclusivity, so it’s worth a brief deep dive.

What is it?

Digital PAYG is a method of paying for rail journeys retrospectively based upon the actual journeys made, using mobile phone-based location tracking.

The rail industry has procured four pilots from four different suppliers:

- East Midlands provided by Trainline, GB’s largest online rail retailer.

- Harrogate – Leeds provided by Tracsis, who also operate the ScotRail ‘Tap & Pay’ scheme, and parts of many card based PAYG schemes.

- Sheffield – Doncaster provided by Fairtiq, who operate Digital PAYG schemes in various locations around Europe.

- Sheffield – Barnsley provided by ECR, who operate Israel’s ‘Rav Pass’ app.

Each trial is open to 1,000 participants and, according to the contract award notice, can last up to 2 years.

How does it work?

At the time of writing, only the East Midlands app delivered by Trainline is live, so I’ve based this on that app. I expect there may be some variation in the detail between the apps, but overall, the concept is likely to be broadly the same.

Instead of buying a ticket before travelling, customers install and register with a Digital PAYG app. A debit/credit card payment authority is set-up to take payments, and a Railcard can be added to the app if held, to ensure that the correct discounts are applied. This is a one-time exercise that doesn’t need to be repeated for subsequent journeys.

The East Midlands pilot is a new feature within the existing East Midlands Railway app (for pilot participants), but the other pilots are expected to involve dedicated apps.

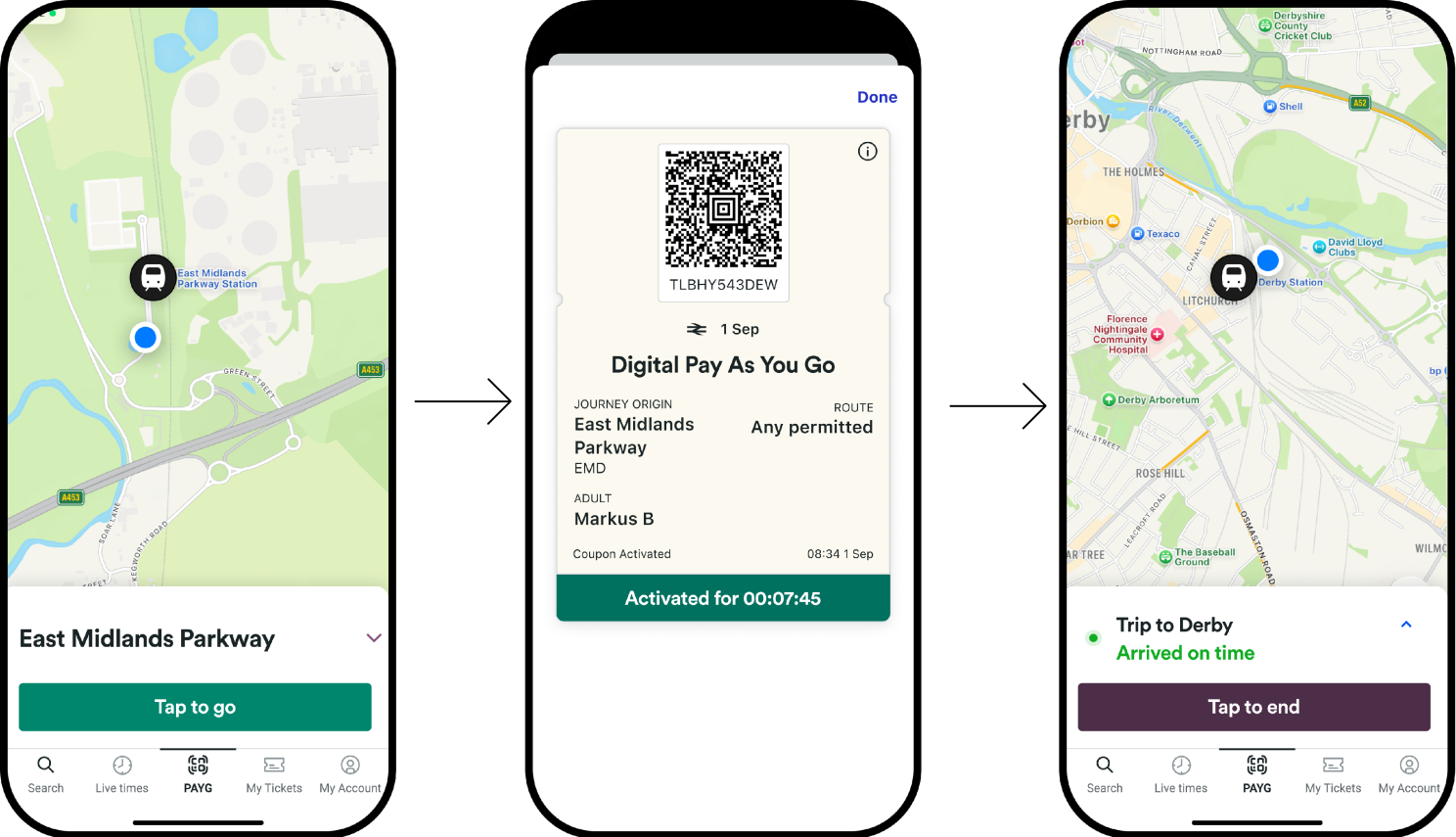

After the initial set-up, customers use the app to “check in” at the start of a journey.

This starts the location tracking and generates a barcode for the customer to use to get through any ticket gates, or to show if a ticket inspector wishes to check their ticket. This uses the same 2D-barcode standard already used on National Rail tickets, and is encoded to permit travel throughout the pilot area.

Once ‘checked-in’ the app periodically uploads location information from the customer’s phone to the DPAYG service. The DPAYG service takes this information, (and possibly other inputs such as scan events from ticket gates or ticket inspections) and uses this to work out where the customer has travelled. This is matched against live train running information, to establish which specific train a customer travelled upon.

At the end of a journey the customer can either ‘check-out’ in the app to end their journey, or if the tracking detects that they have exited the rail network, they will be ‘checked-out’ automatically.

At the end of each day the DPAYG service calculates the cheapest fare(s) for the journey(s) made and charges the customer’s card. This could be one or more single fare, return fare, or a daily maximum fare for the pilot area. For regular travellers it will cap at the weekly season fare for a specific route, or weekly fare cap for the area as applicable.

Will it work?

Although the concept is new to English rail, it is well established elsewhere. SBB has offered this in Switzerland since 2019. Denmark decided in 2023 to replace its national smartcard-based scheme with DPAYG and now has over 50% of all journeys using it. ScotRail also has a live pilot, and there are numerous other regional schemes across Europe. The concept appears to be viable, therefore the focus appears to be on any specific issues in the GB rail context.

What problems does it solve?

There are generally four payment models used in public transport:

- Advance purchase – where a customer books a trip in advance of their time of travel.

- Walk-up tickets – where a customer buys a ticket at the time of travel

- PAYG – where a customer pays retrospectively for specific journeys made.

- Season tickets – where a customer buys a period of travel in advance.

PAYG is primarily an alternative to “walk-up tickets”. It offers four main customer benefits:

- Convenience – there is no longer the need to spend time buying a ticket before travelling.

- Simplicity – there is no need to worry about which ticket to buy, or to understand things such as which trains an “off-peak” ticket is valid on. It removes the anxiety of buying the wrong ticket.

- Flexibility – there is no need to know what journeys you’ll be making later in the day. For example, if your plans change and you get a lift home, you’ve not wasted money on a return ticket.

- Value – you pay the best fare for the actual journeys made. If your journeys are at off-peak times, you just pay an off-peak fare, whereas previously you may have bought an Anytime ticket in case you came home at peak time.

For industry and local authority stakeholders, these customer benefits are seen as important levers for driving greater public transport adoption, removing barriers to people choosing to travel by rail.

In the UK to date, PAYG has mostly been implemented with contactless smartcards or bankcards. London has been a flag-bearer for a concept which has since been rolled out across most bus networks, and the South Wales Metro rail network amongst others (and widely outside the UK).

The use of contactless bankcards for PAYG has been an obvious choice for networks where there were already contactless card readers on buses and on ticket gates at rail and tube stations. It has been very successful for passengers, operators and authorities.

Contactless PAYG, however, has limitations which the Digital PAYG schemes seek to address:

- Cost and speed of rollout – contactless PAYG requires infrastructure at stations: Existing ticket gates have to be fitted with contactless bankcard readers. For areas without ticket gates, “platform validators” need to be installed for customers to tap their card on. Although the cost of the reader hardware has plummeted, installation and maintenance costs, along with payment card security requirements, make it a sizeable commitment and long lead-time. Digital PAYG does not require any infrastructure at stations, so can be rapidly and cost effectively rolled out across the network.

- Operating costs – contactless PAYG is locked into payment card costs: Some agencies, such as TfL, have raised concerns about the costs levied by the payment card industry, which are an unavoidable part of providing contactless PAYG. Whilst the Digital PAYG pilots also use bankcards to collect payment, conceptually in future they could be paired with lower cost payment methods such as Direct Debits or Open Banking.

- Interoperability has been difficult to achieve due to payment card data security: The security requirements associated with payment card data make it difficult to share “tap” information between different operators and schemes. It works ok in contexts such as London where all payment is collected by TfL, but has proven difficult to rollout to areas where there are multiple entities involved. A digital PAYG service can more readily blend products from different modes and operators.

- As contactless schemes are scaled their attractiveness is eroded: As contactless PAYG schemes have grown to cover larger areas, the distance that a customer can travel, and hence the potential maximum fare, gets greater. This requires a greater level of customer trust in the system. If a customer forgets to tap-out, the system doesn’t know if the customer made a short hop, or travelled all the way to the other side of the region. The penalty for forgetting to tap-out has to reflect that uncertainty, and can seem punitive. Digital PAYG largely eliminates the concept of forgetting to tap out, as the system automatically recognises when a customer has left the rail network.

- Contactless has no direct customer interface: Contactless PAYG is purely a payment method, it doesn’t provide any information or means for customers to interact during their journey. Digital PAYG can provide customers with information and support for their journey via their mobile phone. It also makes it easier to handle scenarios such as abandoned journeys. Conceptually it could even nudge customer behaviour: “cheaper off-peak fares start in 10 minutes”.

- Contactless often offers a weak proposition for groups, families and discounts: Most existing contactless PAYG schemes assume “one bankcard = one adult passenger” and charge the bankcard the full adult fare. This makes it a weak proposition for contexts such as travelling as a family, or if the passenger has a Railcard.

Concerns about Digital PAYG

Despite the apparent benefits, the announcement of the Digital PAYG trials has surfaced a number of queries and concerns:

Privacy:

Many of the initial concerns centred around the tracking of user location data. A common question being why the app needs to track throughout the journey rather than simply at the start and end.

I understand that the in-journey tracking is a mix of passenger benefit, fraud mitigation, and improving the quality of the results. The obvious passenger benefit is that if you forget (or choose not) to ‘check out’ at the end of the journey, the app will do that for you. In-turn, this eliminates the need for a punitive “forgot to tap out” penalty. The in-journey location information also allows the service to match your travel to a specific train and apply the fares for that particular service. For example, if an off-peak train was delayed such that it arrived at a peak time, the correct off-peak fare would still be applied.

Whilst the idea of being tracked does inevitably raise an eyebrow, it’s not unprecedented. The journey of any passenger that logs onto on-train WiFi can be tracked by the WiFi provider. Scans of barcode tickets, smartcards and/or bankcards at ticket gates provide a location trail for people using those payment methods. Until recently Google Maps “Timeline” feature recorded a comprehensive trail of the journeys of its users. It’s virtually impossible to use public transport without your movements being recorded by CCTV.

The security and privacy of the data captured is clearly very important, but it would be naïve to think that it is materially out of kilter to what is already captured. As with existing apps, the apps use your location to personalise your experience (e.g. nearest station) but do not track your journeys until you are checked-in.

Accuracy:

Given the complexity of National Rail fares, there have inevitably been questions as to whether the systems can reliably calculate the correct fare. No doubt that’s a key part of what the pilots have been set-up to prove. However, conceptually this is little different to the journey planning that online retailers already do when selling you a ticket before you travel. Instead of you choosing a journey from a journey planner and then calculating the valid fares, the journey is determined by the Digital PAYG engine.

Non-tech adopters:

Not everyone has a mobile phone, and not everyone that has one wants to use it for ticketing. The pilots are entirely optional, no one is being forced to participate. Nonetheless, concerns have been raised that if this was to replace ordinary walk-up ticketing, it would leave some people with no viable options.

I believe it’s highly unlikely that GBR would be looking to fully replace conventional ticketing with Digital PAYG. Some passengers prefer the convenience of PAYG; others prefer the certainty of pre-planning and pre-purchasing a ticket. But, for a very large numbers of rail users that are smartphone users, it will make their rail experience easier.

As an aside, it is estimated that around 2% of working age adults do not have a smartphone, which is similar to the estimated 2% of the UK adult population that do not use banking services. This implies that the level of inclusivity may be similar for both Digital PAYG and contactless PAYG.

Technical failures and flat batteries:

What happens if your battery goes flat, if there’s no mobile signal, or even if the GPS signal is lost? Whilst the precise implementation may vary across the pilots, the general guidance appears to be that a flat battery will be problematic, just as it is with a pre-purchased digital ticket. I’m told that the apps are resilient to intermittent network connectivity, and will upload cached data once connectivity is restored. The loss of GPS signals hasn’t been reported as a significant issue in the countries that have already adopted the capabilities.

Is buying in advance better or PAYG?

Digital PAYG promises to charge the best fare that is available to purchase at the time of travel. There may, however, still be cheaper tickets available for those who book in advance.

That conundrum exists today between advance and walk-up, and is essentially a certainty vs flexibility trade-off. Whilst the cheapest individual fares often come from booking in advance, these usually require travel on specific trains and are non-refundable. Your plans require certainty, and you need to have evaluated options such as season tickets.

PAYG may miss out on the absolute cheapest fares, but you only pay for the actual journeys you made, and daily and weekly best value is automatically worked out for you (no need to compare day tickets and season tickets).

Each model has a place for different customer needs. Having pre-purchase and PAYG in the same app, as EMR have done, provides customers with a single app, whichever way they prefer to pay.

Fraud exploits

There’s been plenty of online discussion about the potential fraud exploits of the proposition, such as what would happen if you disabled location tracking. Whilst little is published about fraud mitigations (for obvious reasons) all the players appear to have prior experience of managing fraud. As the proposition is linked to a customer, their mobile phone, and their payment method, patterns would no doubt soon emerge of any customers systematically abusing the system.

What next?

“this could be one smart ticketing trial that really does lead to something big” - Jonathan Bray

Often National Rail and local transport have quite a different focus on ticketing needs. It has been interesting, therefore, to see local transport thought leaders such as Jonathan Bray and John Henshall also expressing interest in DPAYG.

Could we have finally found a revenue collection mechanism that works well for customers of both National Rail and local transport, and that can be rolled out in a timely manner within budget and structural constraints?

To date GBR, via its “Fares Ticketing and Retail” programme, has taken quite a hands-on approach to procuring and overseeing the pilots in rail. The next phase, however, might benefit from a more open and standards based approach that enables a wider ranger of parties to leverage the capabilities:

- Regional authorities looking for solutions that can straddle bus, light rail and National Rail, and that can work beyond authority boundaries.

- Regional “TiCos” (ticketing companies) looking to complement and evolve from their existing pre-purchase multimodal pass products.

- Specialist rail retailers with established customer bases, such as Trainline.

It would be a missed opportunity if the pilots simply led to a long procurement process, that precisely defines an app for one specific use case, that would no doubt be out of date by the time it launches.

Digital PAYG has the potential to transform the experience for many of those who pay for travel on the day. Whilst there will still be a strong role for pre-paid ticketing, it could be a paradigm change on a par with the introduction of Oyster, mobile ticketing or contactless.